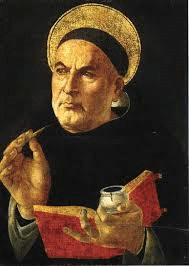

Richard Dawkins opens his chapter on surveying arguments for God’s existence by quoting from Thomas Jefferson that “a professorship of theology should have no place in our institution.” Instead of demanding proof for this statement, Dawkins turns his gaze towards the proofs of another Thomas, St. Thomas Aquinas. With amazing brevity he is able to debunk the first three of Aquinas’ five ways in a mere two paragraphs. Three quarters of a millennium is swept aside by a Professor of Public Understanding in Science at Oxford in a mere two paragraphs relegating one of the greatest philosopher’s arguments to the dustbin of history. Unfortunately, upon even a cursory examination the Professor’s rebuttal falls rather flat. In fact, for those who have actually read and studied Aquinas’ five ways you get the impression that Dawkins is talking about a completely different argument.

Dawkins might advocate removing theology from the standard course of study, but he has also thrown the philosophical baby out with the theological bathwater. He and his “New Atheist” friends may be competent scientists, but they are terrible philosophers. Revealing hubris more than truth, they are particularly adept at knocking down straw men. Rather than putting forth the intellectual effort to grapple with the real argument they dismiss it with a healthy dose of acerbic wit. So despite the fact that they are a loud gong signifying nothing, they make enough noise that they get the attention of many people who thoughtlessly regurgitate their arguments.

Dawkins and the First Way

Here is how Dawkins describes Aquinas’ first way:

The Unmoved Mover. Nothing moves without a prior mover. This leads us to a regress, from which the only escape is God. Something had to make the first move, and that something we call God.

Candidly, if this did accurately describe Aquinas’ proof, then he would be warranted in his criticism when he says, “They make the entirely unwarranted assumption that God Himself is immune to the regress. Even if we alow the dubious luxury of arbitrarily conjuring up a terminator to an infinite regress and giving it a name, simply because we need one, there absolutely no reason to endow that terminator with any of the properties normally ascribed to God: omnipotence, omniscience, goodness…”

Of course this is not at all what Aquinas was arguing in what he called the “more manifest way of the argument from motion” (ST I, q.2 art.3). When Aquinas speaks of “motion” or “movement” he is not talking about physical bodies moving from one place to another specifically. Dawkins is not alone in his linking this argument with what he calls a “big bang singularity” or anything like a cue ball hitting one ball that then knocks another ball into the pocket. Rather than locomotion (i.e. motion though space), Aquinas is concerned with motion in the broader sense of change. Change for Aquinas is the actualizing of some potential. This is why this particular argument is the most obvious for Aquinas—we see change everywhere we look. All change requires a changer, that is some actualizer to a given things potential. Lukewarm water is potentially cold, but in order to become cold, it must come into contact with something that is actually cold. This is nothing other than the principle of causality, a principle that a scientist like Dawkins must readily accept.

“All change requires a changer” sounds like just a rewording of what Dawkins said, except by examining change more broadly Aquinas is concerned not of a linear change like tracing the Big Bang to a Big Banger (that would be just locomotion) but having a vertical understanding change in the here and now. An example might help to understand this.

The keyboard on this computer has the potential to put the letter R in a document. But in order for that potential to be actualized, it must have someone type it. But for someone to type it, it must be open and on a desk. In order for the desk to hold it, it must be sitting on a floor. In order for the floor to hold the desk holding the computer it must rest on joists that rest on a foundation that rest on the ground. The earth is held in place by the sun which in turn is held in place by the other heavenly bodies and so forth. Each link in the chain reveals another actual being that was only potential until something else actualized it.

Notice that the regress then is not backward in time, but here and now. Notice also that no infinite number of desks, for example, could support the computer. Each desk cannot derive its power to support the computer on its own. It must borrow that power from something else. In short, even an infinite number of desks must sit upon something unmovable, or an “unmoved mover.” No number of desks can support themselves. So, rather than making the “entirely unwarranted assumption that God Himself is immune to this regress” Aquinas shows the necessity of some being that has no potential and is pure activity. Dawkins has failed to even address the argument but simply labels it “an unwarranted assumption.” It is not an assumption but something that Aquinas has proven. Perhaps he is mistaken, but you must deal with the argument as it is. You have to disprove the principle of sufficient reason, which would also throw science as a discipline out with it. Dawkins and many of those who repeat what he says instead takes the intellectual high road and mocks what is a very serious challenge to his worldview. Rather than relying on reason as he purports to do, Dawkins instead prefers faith in his unprovable assumption that God does not exist.

But Must We Call It God?

Reading between the lines of what Dawkins says it might be that he rejects calling this necessary being God. He mentions that “there is no reason to endow the terminator with any of the properties normally ascribed to God.” This again reveals his unwillingness to actually engage the argument and instead prefers to play silly games like pitting omniscience and omnipotence against each other.

Certainly there are limits to what reason can tell us about God. To fully reason to God would make us God. For those invited to divine participation they must rely on Divine Revelation to know that He listens to prayers and forgives sins (two that Dawkins mentions). But once reason tells us that He exists and that He is omnipotent, omniscient, and omni-benevolent then faith can tell us the rest.

Rather than having “no reason to endow” God with these attributes, we have good reason from what has already been said. Because He is the source of all change or motion, He must be all-powerful. Since the principle of sufficient reason tells us that the effect must be in the cause and that the thing known must be in the knower, the nature or essence of all things must be in the cause of them. Therefore God is omniscient. Finally, because He lacks nothing (i.e. having no potential) and the actualizer of all things He must be omnibenevolent.

Aquinas closes his first way with the statement, “therefore it is necessary to arrive at a first mover, put in motion by no other; and this everyone understands to be God”( ST I, q.2, art. 3). Everyone? Perhaps Aquinas was wrong. More likely though is that there are many who refuse to acknowledge God’s existence by doing the intellectual leg work to confront challenges to their worldview.