In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, Edmund Burke comments on the loss of honor that came as a result of the French Revolution. Concerning Marie Antoinette, Burke writes,

Little did I dream that I should have lived to see such disasters fallen upon her in a nation of gallant men, in a nation of men of honour and of cavaliers. I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators, has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished for ever. Never, never more, shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom. The unbought grace of life, the cheap defence of nations, the nurse of manly sentiment and heroic enterprize is gone! It is gone, that sensibility of principle, that chastity of honour, which felt a stain like a wound, which inspired courage whilst it mitigated ferocity, which ennobled whatever it touched, and under which vice itself lost half its evil, by losing all its grossness.

Honor once lost, like any other virtue, is not easily regained. It is especially hard to regain in a culture that is actively hostile to it.

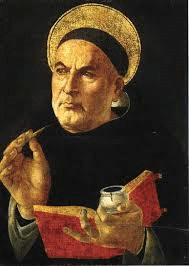

Honor, as St. Thomas Aquinas defines it, “is the reward of every virtue… it follows that by reason of its matter it regards all of the virtues” (ST II-II Q. 129 Art. 4). Thus, it is clear that honor comes from virtue. In order to be truly honorable, a man must be virtuous. Our culture has, in large part, rejected the traditional idea of virtue. There is much talk about rights and what we are owed, but little discussion about duty. Men are encouraged to extol the virtues of kindness and inclusivity, and women, on the other hand, are told that expressing traits like “nurturance” and “family-oriented values” are just mere preferences and not virtues. As always, the devil is in the details. A man should be loving and caring, but if he places kindness and inclusivity above all other virtues then the family and, by extension, society, will suffer. Certainly, kindness and inclusivity would not have saved Marie Antoinette from the guillotine. And families do not need women who prefer to be nurturing and selfless, but women who are nurturing and selfless. There will be, however, some who will object to this and say that traditional notions of honor and virtue are outdated and bigoted. So, naturally, the question becomes, “Why should we care about honor, aren’t we better off without it?”.

There are a couple of approaches one could take towards answering this question. The first would be to ask what will replace the role that honor had in society? What is beyond honor and virtue? Alasdair MacIntyre explores this question in his book After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Of a society that has lost its vision of honor and virtue he writes,

In a society where there is no longer a shared conception of the community’s good as specified by the good for man, there can no longer either be any very substantial concept of what it is to contribute more or less to the achievement of that good. Hence notions of desert and of honor become detached from the context in which they were originally at home. Honor becomes nothing more than a badge of aristocratic status, and status itself, tied as it is now so securely to property, has very little to do with desert.

A society that abandons honor does not get egalitarianism. Instead, it gets aristocracy and credentialism.

For the second approach, one might ask if tearing down virtue and honor would also threaten other societal goods. Failing to examine this question would be like removing a wall in a house without first determining if it is load-bearing. Unfortunately, leaving honor in the past has not been without consequence. Honor is the basis for magnanimity. Aquinas identifies this connection: “Now a man is said to be magnanimous in respect of things that are great absolutely and simply, just as a man is said to be brave in respect of things that are difficult simply. It follows therefore that magnanimity is about honors” (ST II-II Q. 129 Art. 1). In 2020, Ross Douthat wrote a book called The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success about how and why our society has, in many ways, stopped advancing. While his hypothesis is beyond the scope of this article, the phenomenon he is discussing is germane to the point. There has been a societal decline in the desire to do great things. This stems directly from a change in societal value. As MacIntyre pointed out, society values the vain status associated with honor rather than the virtue from which honor is derived. Not only is magnanimity a virtue and therefore necessary for human flourishing, but society needs it. Magnanimity landed on the moon, it sailed to new worlds, it wrote poems and epics, it built planes, and made countless discoveries and inventions. So rather than resent success and laugh at honor, we should have the courage to ask ourselves if we are here on this earth for something great. Perhaps there really is something great in store for each and every one of us if we would but have the courage and magnanimity to pursue it. And even more terrifying is the possibility that part of the greatness God wishes to bring to the world can only be brought through you. Sure, God can bring goodness out of anything, but there may be good that never comes if you abandon honor and magnanimity. In closing, I would like to turn to Pope Benedict XVI who so eloquently reminds us of this truth: “The ways of the Lord are not easy, but we were not created for an easy life, but for great things, for goodness”.