At various points along the Christian journey, believers must confront questions related to the true identity of Jesus Christ. Those who persevere and grow, learn to plow through them one by one and in so doing, more deeply discover the personality of the Incarnate Son of God. Among these questions there is one that is particularly illuminating, especially because it deals with something that has very practical implications for our own spiritual life. Articulated in various forms, the question goes something like this: “If Jesus was God, then why did He pray?”

The question of the identity of Jesus is not just something that plagues the neophyte, but it was also a question that the Early Church had to face head on. Although worked out over centuries, we can summarize their findings by articulating a single principle—the distinction between person and nature.

The Person/Nature Distinction

In his encounter with individual objects in the world, man is confronted with a powerful question: “what is this?” The answer as to the thing’s what-ness is its nature. But a nature determines not just what a thing is, but what a thing can do. A bird can fly because it has a bird nature, an elephant, because it has an elephant nature cannot. Man can pray because he has a human nature, but a mantis’ nature limits him to merely posturing.

When the object of one’s inquiry is also a subject, this innate tendency gives rise to a second question: “who is this?” No longer concerned with the fact that the object has a human nature, the interlocutor turns their gaze to the person himself. The human nature may determine what the person can do, but it is always the person who performs the action. The nature, in a very real sense, limits what the person can do.

When we extend the person/nature distinction to the Incarnation, it is especially helpful in addressing our initial question. The Divine Son, the Word Incarnate is a Person, but He is a Person Who has two natures or two modes of operation. At any given time we can observe Him using one of those two natures. He can change bread and wine into His Body and Blood using His Divine Nature, but He can pray using His human nature. But in either case, it is always the same Divine Person who performs the action. He simply has two modes of operation. This is theologically referred to a the Hypostatic Union.

Christ then prayed using His human nature and not His divine. He prayed as Man and not as God. And Christ’s prayer, because it is the prayer of a Divine Person, is one of the means that He Providentially determined would be the cause of certain graces to flow into the world. And in that way His prayer was always effective. Two examples from His Passion are particularly instructive in this regard.

Two Dominical Examples

The first example of Christ praying shows us something that we naturally intuit. If Christ prays as man and nevertheless it is God Himself who utters the words, then we should expect His prayer to do something. During the Last Supper He tells Peter that “Satan has demanded to sift you like wheat. But I have prayed for you that your faith will not fail so that when you have turned back you will strengthen your brothers” (Lk 22:32). It is Our Lord’s prayer, expressed in an absolute manner, that is the cause of Peter’s repentance.

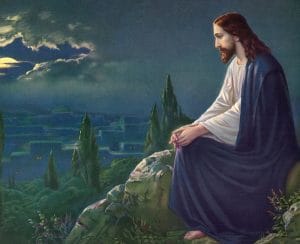

The second Example shows us something deeper that if we are not diligent we might miss. In the Garden of Gethsemane we find Christ, again in His human nature, praying that the cup be removed from Him only if it be in accord with the Divine will. In so doing, Christ is praying in a conditional manner as far as the direct outcome is concerned. But His prayer is always effective so that it accomplishes something, namely that those who are united to Him through faith and charity be awarded the graces for us to pray boldly and to endure those moments when prayer is not answered according to our will but the will of the Father.

What this shows us is not just that Christ’s prayer was infallibly effective, but that our prayer is really just a participation in His prayer. Every grace that we are given through our prayer was first merited by Christ in His. Because He is God, He saw every instance of our prayer, all of our intentions, spoken and not, when He prayed. It was in His moments of prayer that He won the necessary graces for us. It remains for us to simply enter into His prayer with Him and receive what He intended to give us when He invited us in to begin with.

St. Cyril once said, “that which was not assumed, was not redeemed.” What he meant by this is that Christ took to Himself a true human nature with all its needs and redeemed every aspect of our nature. This includes our prayer. Christ prayed so that our prayer was efficacious. This union of Christ’s prayer with our own helps us to understand exactly what we mean when we pray “through Christ Our Lord.” Our prayer insofar as it is genuine is always through His prayer. He lives forever to intercede for us because time and eternity have met in the Incarnation.

Most of us are moved deeply by the Gospel accounts of Christ praying even if we are not able to articulate why. If we merely see it as an example, which of course it is, then we will miss the invitation. Christ’s prayer is an invitation for all of us to come and pray with Him. He may have gone off alone to pray, but each one of us was there with Him.