Pope St. Pius X once said that all errors in the practical and social realm were founded upon theological errors. The Saintly Pontiff’s maxim seems almost common-sensical, so much so that, we can easily overlook it. Ideas have consequences and bad ideas, especially bad ideas about Who God is and who man is, have bad consequences. As a corollary then we might say that it is impossible to fix the bad consequences without rectifying the bad thinking. One such bad idea, namely that all authority in the political realm comes from the people, has had the devastating consequence of erecting a “wall of separation between Church and State” leading to the loss of many souls.

The Source of Secular Authority

The properly Christian understanding about the source of secular authority is that it comes from God Himself. This is made clear by Our Lord during His trial in which He tells Pilate that “You would have no power over me if it had not been given to you from above” (John 19:11). In his usually blunt manner, St. Paul echoes the same principle when he reminds the Christians in Rome to “Let every person be subordinate to the higher authorities, for there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been established by God” (Romans 13:1). God as Creator and Sustainer of all Creation is also its supreme authority. All authority is exercised in His name and flows from Him. Kings, emperors and presidents all derive their power to rule from Him and it is only for that reason that they also have the power to bind consciences for just laws.

Summarizing the Church’s understanding of secular authority, Pope Leo XIII instructs the faithful that “all public power must proceed from God. For God alone is the true and supreme Lord of the world. Everything, without exception, must be subject to Him, and must serve him, so that whosoever holds the right to govern holds it from one sole and single source, namely, God, the sovereign Ruler of all. ‘There is no power but from God’” (Leo XIII, Immortale Dei, 3).

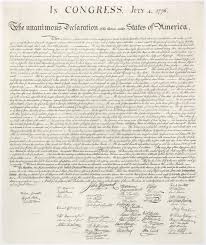

This view of authority flies in the face of countries such as the United States. Rather than authority from above, it is based on authority from below. Known as popular sovereignty, this founding principle is first articulated in the Declaration of Independence where Jefferson told the King that legitimate governments are those ‘‘deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed.’’

Luther’s Error and Its Modern Consequences

So ingrained in the modern mind, we might not even realize that it is opposed to the correct understanding of the source of secular authority. It would be easy to blame this on the Enlightenment, but the error pre-dates even the Enlightenment and Social Contract Theory. Instead the error is rooted in Luther’s revolution in which he rejected the authority of the Church. Leo XIII points this out in his encyclical Diuturnum by drawing a line from the so-called Reformation to Communism and nihilism: “…sudden uprisings and the boldest rebellions immediately followed in Germany the so-called Reformation, the authors and leaders of which, by their new doctrines, attacked at the very foundation religious and civil authority; and this with so fearful an outburst of civil war and with such slaughter that there was scarcely any place free from tumult and bloodshed. From this heresy there arose in the last century a false philosophy – a new right as it is called, and a popular authority, together with an unbridled license which many regard as the only true liberty. Hence we have reached the limit of horrors, to wit, communism, socialism, nihilism, hideous deformities of the civil society of men and almost its ruin” (Leo XIII, Diuturnum, 23).

If we follow the logic we will see why this is a necessary consequence. Animated by a Protestant mentality, each person treats directly with God without any intermediary. Each person becomes an authority in himself and therefore any authority that is to found in a social body is by his consent. In essence then it eliminates the Kingship of Christ in the temporal realm and completely privatizes religion.

This helps to explain why most Protestants see no problem in the current belief in a “Wall of Separation” between Church and State. It was Luther himself that was the intellectual predecessor: “[B]etween the Christian and the ruler, a profound separation must be made. Assuredly, a prince can be a Christian, but it is not as a Christian that he ought to govern. As a ruler, he is not called a Christian but a prince. The man is a Christian, but his function does not concern his religion. Though they are found in the same man, the two states or functions are perfectly marked off one from the other, and really opposed.” Both the Christian Prince and the Christian citizen were to live their lives in two separate realms and, ironically enough, not submitting to God in either since they also rejected His Kingship in the Catholic Church. Once the divorce is complete, all types of political errors begin to take hold. Luther’s insistence on individual and private judgement leads directly to Locke, Rousseau, and Marx. One theological error leads to many political errors.

The Church then will always find conflict with the modern state until this error is corrected. The modern State hates the Catholic Church because it is an existential threat because it seeks, or at least ought to seek, to acknowledge God’s authority in the temporal realm. It is also the reason that Catholics ought to make the best citizens. They see no conflict between Church and State because both have their authority rooted in God Himself and to obey either is to obey God.