In the second chapter of his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul details his encounter with the first pope upon his visit to Antioch. The Apostle to the Gentiles called St. Peter to task for withdrawing from the Gentiles and eating only with the Jews out of fear of offending the latter. Knowing that their faith was weak, St. Peter did not want to scandalize them and so, out of a misguided sense of charity, he pretended to agree with them. St. Paul was, of course, right. St. Peter failed pastorally to shepherd his entire flock. The truth can never be a source of scandal and it is no act of charity to water down the faith.

This event is favorite for non-Catholic apologists for arguing against the primacy of Peter. After all, they reason, if Peter is the infallible head of the Church then how could Paul question him and find in him in error? Therefore, the Apostles were all equals and the Catholic doctrines surrounding the papacy are false. Of course, they read far beyond what happened. Nowhere does St. Paul challenge St. Peter’s authority to rule, only his exercise of that authority.

Putting aside its apologetical value, this particular passage serves as a guiding light for Church management, especially in times when error is being propagated by those in authority. One can see the great wisdom of the Holy Spirit in inspiring St. Paul to recount this event because it serves as an example for both prelates and their subjects. From the perspective of the prelate, we are given an example of humility so as not to disdain correction from those who are “lower” than them. From the perspective of the lay faithful it provides an example of both zeal and courage to correct those in the hierarchy.

What is Scandal?

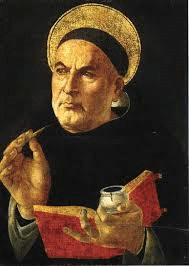

First, a word about scandal. In English this word tends to be understood as referring to an action that leads to public disgrace. But in the theological sense the word has a more precise meaning. The word comes from the Greek skándalon which means “a stumbling block.” Specifically it refers to some action that creates a moral stumbling block for another person. St. Thomas defines it as “something less rightly done or said, that occasions another’s spiritual downfall.” The Angelic Doctor goes on to categorize scandal into two types: active and passive. Active scandal, that which has as its reward a millstone, is “when a man either intends, by his evil word or deed, to lead another man into sin, or, if he does not so intend, when his deed is of such a nature as to lead another into sin: for instance, when a man publicly commits a sin or does something that has an appearance of sin.” Passive scandal is when “one man’s word or deed is the accidental cause of another’s sin, when he neither intends to lead him into sin, nor does what is of a nature to lead him into sin, and yet this other one, through being ill-disposed, is led into sin” (ST II-II, q.43, a.1).

In short, scandal always pertains to an act that is in some way public in the sense that many people know about it. One should never make public what was strictly done in private as the accuser would then be the cause of scandal rather than the perpetrator. What happens in private should both remain and be corrected in private. But in either case it is an obligation of charity to issue a correction.

The Obligation to Correct

Why is there an obligation? By way of analogy, St. Robert Bellarmine, a Doctor of the Church helps to illuminate why this is:

“As it is lawful to resist the Pope, if he assaulted a man’s person, so it is lawful to resist him, if he assaulted souls, or troubled the state, and much more if he strove to destroy the Church. It is lawful, I say, to resist him, by not doing what he commands, and hindering the execution of his will.”

While the saint mentions the Pope specifically, what he says applies to Bishops, Priests and Deacons. If you saw a prelate beating a man physically you would stop it and you should do likewise if he is beating him spiritually. St. Thomas Aquinas goes a step further saying that it is an act of charity not just towards the rest of the sheep but also towards the prelate as well because the scandalous behavior puts the prelate’s soul in great danger. He, who has been given much, will have to answer for much.

St. Thomas says that “like all virtues, this act of fraternal charity is moderated by due circumstances.” What he means by this is that we must not only be aware of our obligation, but also the manner in which we exercise that obligation. While criticizing a prelate does not make you “more Catholic than the Pope” the manner in which you do it should make you just as Catholic as the Pope. That is we should never forget that the operative word is charity. This means that there are certain rules that ought to govern our interactions.

The Code of Canon Law (Canon 212) says that the faithful may legitimately criticize their pastors but that it must always be done “with reverence toward their pastors.” This means that the criticism should first of all be done in private so that the pastor has an opportunity to correct himself. This maintains the dignity of both their office and their person.

There are times however when the pastor does not correct himself or that meeting with him in private is not possible (not everyone can get a papal audience for example). It may also be that the act or word poses such a danger to the faithful that a public rebuke is necessary. In other words, it may be necessary like St. Paul to “withstand him to his face.” St. Thomas says that if the faith were endangered a subject ought to rebuke his prelate even publicly on account of the eminent danger of scandal (ST II-II q. 43 a. 1 obj.2). This is why it is important to understand what constitutes scandal and what does not. In any regard it may be necessary to “correct” the pastor in public out of, not just fraternal charity, but justice because the faithful have a right to the content of the faith in a clear and undiluted manner. But still it must be done with gentleness and reverence for his office.

Before closing a word about the response of pastors. Augustine says that Peter “gave an example to superiors, that if at any time they should happen to stray from the straight path, they should not disdain to be reproved by their subjects.” Very often pastors think themselves above criticism from mere lay persons regardless of how qualified those lay persons are. They remove the emphasis away from the truth as spoken onto the one speaking the truth. Unfortunately the fraternal charity is not likewise met with pastoral humility. It is this spirit that causes many lay people to remain quiet not confident enough that they could defend the Church’s position, especially when they are likely to be met with hostility.

In Loss and Gain, Blessed John Henry Newman’s fictional account of the conversion of a man from Anglicanism to the Roman Catholic Church, the protagonist Redding was drawn to the Church by its consistency. While he could ask ten Anglican Priests to explain a particular dogma and get ten different answers, he would get the same answer from ten Catholic pastors. Those days of consistency are no longer among us, a phenomenon that can only be corrected when the entire Church, lay and clergy, take ownership of the Faith and fear not to correct wayward Shepherds.