The account of the creation of Adam and Eve in Genesis has often been labeled as the genesis of misogyny by feminists. The opening account in the Bible has become for many the point where they close the book. Therefore it behooves us to know how to respond to such a charge. In so doing, we will, like Adam who found an unlikely “helpmate” in Eve, we will turn to what many would consider a more unlikely helpmate—St. Thomas Aquinas.

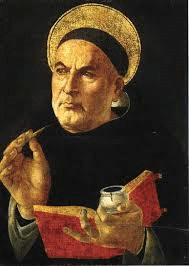

Using St. Thomas as a helper to dismiss the charge of misogyny require some explaining. For many people this would be like asking David Duke to help defend proper race relations. But there is good reason to turn to the Dumb Ox for help on this. Too often skeptics will dismiss the entire corpus of his teaching because the Angelic Doctor is a “misogynist.” Following the teachings of Aristotle, St. Thomas saw women as “misbegotten males.”

It bears mentioning however that if he was wrong about women, then this does not mean he was wrong about everything, or even anything else. All this would prove is that he was not infallible and was capable of making mistakes. Like all of us, he too was prone to unquestionably accept some of the prevailing views of his day. To have a blind spot, does not make one blind. Should the entire economic theory of Adam Smith be thrown out because “woman are emotional and men rational.”? What about John Locke’s political theory because he justifies slavery? Living in the glass house of a multitude of errors in our own day, we should be careful to throw stone.

St. Thomas Aquinas: Patron Saint of Misogyny?

This particular case is worth examining however because St. Thomas does not wholly swallow the prevailing viewpoint. While he wrote about women (including his great esteem for Our Lady) in numerous places, he is usually, as mentioned above, accused of misogyny because of what he wrote in a single place when called woman a “misbegotten male.”

In seeking to examine the origin of woman, St. Thomas first asks should the woman have been made in that first production of things (ST I, q.92, art.1)? He answers in the affirmative, but the first objection he mentions is that of the Philosopher, that is Aristotle:

“For the Philosopher says (De Gener. ii, 3), that ‘the female is a misbegotten male.’ But nothing misbegotten or defective should have been in the first production of things. Therefore woman should not have been made at that first production.”

Note first that this he has listed as an objection to his own viewpoint. Obviously it was not his own. In his reply to this objection he shows why he does not agree completely with Aristotle. It is worth citing the entire response in order to put the myth of his woman hating to rest.

“As regards the individual nature, woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force or from some material indisposition, or even from some external influence; such as that of a south wind, which is moist, as the Philosopher observes (De Gener. Animal. iv, 2). On the other hand, as regards human nature in general, woman is not misbegotten, but is included in nature’s intention as directed to the work of generation. Now the general intention of nature depends on God, Who is the universal Author of nature. Therefore, in producing nature, God formed not only the male but also the female.”

Notice that he agrees with Aristotle about the “misbegotten” part, but only on a biological level. The prevailing view of reproductive biology was that the sperm produced only male offspring, and that when this did not happen it was because something interfered with it. But St. Thomas goes to some length to say that woman is not a mistake of any sort, but directly willed by God. Men and women, in St. Thomas’ view, are equal in dignity, even if there are some accidental inferiorities (such as physical strength) between the two. We shall return to this idea in a moment when we speak of Eve’s origin.

Eve and Adam’s Rib

In the second chapter of Genesis, speaks of the mysterious origins of man and woman. The man, Adam, is made from the dust of the ground infused with a spirit. The woman is “built” from the rib of the man. (Gn 2:21-22).

Much of the creation account uses metaphorical or mythical language, but that does not mean it is entirely composed of metaphor. In fact, the Church is quite insistent that we understand Eve being formed from the rib of Adam literally. This is one of the three truths of man’s origins from revelation that the Church insists must be safeguarded from any encroachment by a Theory of Evolution. Strictly speaking, if creatures are always evolving, there is always a relationship of inferior to superior. If woman and man evolved from different individuals, evolution would lead them eventually away from each other. Survival of the fittest would mean that one would necessarily become superior to the other. But if they share one common origin, one common nature, then they will necessarily be equals. By insisting that woman is taken from man, the Church is affirming this essential equality between man and woman; equal dignity such that any differences are not essential but only accidental.

This view is pretty much what we saw in St. Thomas’ explanation of why the understanding of woman as a misbegotten man is inadequate. He goes on to further say that,

“It was right for the woman to be made from a rib of man…to signify the social union of man and woman, for the woman should neither “use authority over man,” and so she was not made from his head; nor was it right for her to be subject to man’s contempt as his slave, and so she was not made from his feet” (ST I, q.92, a. 3).

By removing the rib from Adam, God also would have exposed Adam’s heart to Eve, a truth that becomes clear when we examine the act of creation of the bride of the First Adam, with the bride of the Second Adam. Just as Adam fell asleep and the raw material of his bride came from his side, so too when the Second Adam fell asleep that the raw material that God would form into His Bride came forth.

This exposure of Adam’s heart has not just a mystical meaning, but a natural one as well. It is an expression of the truth that “it is not good that man should be alone.” Pope St. John Paul II mentions this when he discusses the meaning of Adam’s rib during his catecheses on the Theology of the Body. In naming the animals, man experiences what the Pope calls Original Solitude, in recognizing he is fundamentally alone among creation. In the creation of Eve, he ecstatically experiences that he was made for another, that is, he was made to love—“this at last is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh!” In other words, Eve being taken from the rib of Adam reveals that the two ways of being human somehow complete each other. As John Paul II puts it, the rib reveals masculinity and femininity as “two complementary dimensions…of self-consciousness and self-determination and, at the same time, two complementary ways of being conscious of the meaning of the body” (TOB 11/21/79). Adam’s recognition of Eve as somehow his equal and yet wholly other is a summons to love.

There is certainly a rich symbolism attached to the idea of Eve created from the rib of Adam, but must we really interpret it literally? Literal interpretation affirms another very important, and very Catholic, principle related to God’s Providence. God, being totally free, could have fashioned Eve in any manner He wanted. But He chose this way not because it was a symbol, but because it was a sacrament. It brought about and revealed the things that it symbolized—the unity, equality and love that each of the symbols we mentioned pointed to. All of creation including the human nature of Christ is meant to reveal God to us. Therefore nothing that He has made can be taken at face value as “only this” or “only that.” Everything that is, means something. God does not need to use symbolic language because everything that He creates is in some sense a symbol.

The accusation of misogyny in the origins of man and woman is really an accusation of Christianity not being Christian. Prior to the “evolution” of Christian culture, women were always viewed as somehow inferior to men. It is only when Christianity became the prevailing worldview that the essential equality of men and women became the norm. Now, revisionists would have us believe that the hand that fed us, actually poisoned us, by feeding us healthy food. The account of the creation of Eve reveals the dignity of woman and is not misogynistic.