When the Catechism of the Council of Trent was published in 1566, it contained a warning regarding the Sacrament of Confirmation:

If ever there was a time demanding the diligence of pastors in explaining the Sacrament of Confirmation, in these days certainly it requires special attention, when there are found in the holy Church of God many by whom this Sacrament is altogether omitted; while very few seek to obtain from it the fruit of divine grace which they should derive from its participation.

As much as this was true is 1566, it is probably even more so today. Most Catholics operate under a false understanding of what the Sacrament is and does and therefore fail to make use of it. Given the direction our culture is going and the need for strong Christian witness, it is time to examine this Sacrament once again so we can make use of the supernatural power that God provides us.

The Purpose of Confirmation

The most common misunderstanding about Confirmation is attached to its purpose. Most see it correctly as somehow completing the Sacraments of Initiation (Baptism and the Eucharist), but assume it just involves accepting responsibility for your faith. It is given when someone is old enough to make a decision for themselves about whether they are going to accept the faith they were baptized into. While it is often received after someone has reached the age of reason, this accepting of responsibility for your faith would not make it a Sacrament. Sacraments are first and foremost the work of God.

All of the Sacraments confer sanctifying grace, but each one also bestows a unique grace called “sacramental grace.” Three of them, Baptism, Holy Orders, and Confirmation, also bestow an indelible mark on the soul called a character. In addition to serving as a mark of distinction, it also acts as a sign that denotes a certain duty. Think of it as a badge on the soul that deputizes us to perform a certain office. It also disposes us for the reception of actual graces. Even more than that, it gives us a right to all the actual graces that are necessary to fulfill that particular office.

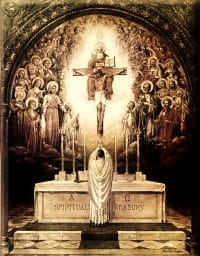

The sacramental grace that is bestowed on us in Confirmation is the “power of the Holy Spirit” by which we are enabled to believe firmly and profess boldly the Gospel. Think of Peter on Pentecost and afterwards. It marks us as soldiers for Christ and causes the necessary growth in us to serve on the front lines, wherever the Front that God sends us may be. It also imposes on us the duty to witness to the Faith. Because God never gives a mission without the necessary grace to fulfill that mission it also gives us the right to those actual graces we need to fight for Christ and His Church.

There is a danger in leaving this on an intellectual level. But we need to realize (i.e. make real in our own lives) what Confirmation does to us and how God puts Himself in a position in which He owes us something. I have been marked as a Christian witness at the core of my being and this mark obligates me to profess the One Who has marked me. It is no cosmetic change, but a change that will last forever. Because I bear this mark, God owes me all the actual graces that I need. I can count on them when I need them because He is just. The challenge is to live with this realization and allow my courage to increase daily—the grace of Confirmation perfects each of our seemingly small acts of witness until we are boldly professing the Truth to all who need to hear it. How different my encounters will be if I live with this in mind rather than relying on my own strength? How much confidence will I gain?

As I walk down the street no other man may see the mark, but this mark can be seen by our real enemies. It becomes a bull’s-eye of sorts in which they now take sharper aim at us. This is why we must recall that the Greek word for witness is martus, from which we get the word martyr. Ultimately Confirmation is the Sacrament of Martyrdom.

When the Levitical priests were preparing burnt offering sacrifice to God, they always laid their hands upon its head (c.f. Lev 1:3 and Exodus 29:10, 15). This is why a Bishop, who has received the fullness of the Priesthood of Jesus Christ, is the ordinary minister of the Sacrament. By laying his hands on the confirmand’s head, he is setting that person aside as a sacrifice to God. This is why it is so important for us to enter the Sacrament with eyes wide open and having a proper understanding what it actually empowers us to be. It fully conforms us to Christ by marking us a victims. We are no longer just adopted sons and daughters through Christ, we now become more fully conformed to Him as victims.

When Confirmation Should Happen?

Before closing, a word about who should receive the Sacrament. With all the Sacraments, there is an ever-present danger of treating them like magic. We grasp objectively what they are—essential channels of sanctifying grace—but spend little time worrying about the subjective dimension. In other words, we don’t necessarily ask whether the person is really ready (not just superficially able to tell you what the 7 Gifts of the Holy Spirit are) to receive that grace. It is given to many teens in the hopes that something “sticks.” Then we are surprised when we don’t see any real change in the Confirmandi and the Church as a whole. Rather than quibbling over the proper age to give the Sacrament, what if we spent the time really preparing them? Helping them develop a true prayer life, a true Sacramental life (including regular reception of the Sacrament of Confession) and forming them to battle the enemies of the Church. A Catholic boot camp of sorts to train the next generation of Christian soldiers.

The need for credible witnesses to the Faith has grown dire in the past fifty years and one can imagine that it will increase even more in the immediate future. In response to this, many in the Church have called for a New Pentecost. In truth however a New Pentecost is not needed—the grace of the Sacrament of Confirmation extends the same power of Pentecost through time. What is needed is a greater emphasis on the necessity of this Sacrament. We should be giving it sooner to children rather than later, especially since children today seem to face a unique set of challenges that could lead to a loss of faith earlier in their lives than ever before. This starts however by spreading an understanding of this virtually untapped source of supernatural power so that we can truly bring about the fruit of Pentecost today.