In the midst of his battle against the Arians, St. Athanasius once pithily said, “that which Christ did not assume, has not been healed.” The point that the Father of Orthodoxy was making was that Our Lord assumed the entirety of our human condition in order to redeem and renew us (2 Cor 5:17). He did not just generically redeem our actions, in lived them in order that they might be sanctified. He became a worker, in order to redeem our work. He entered a family in order to redeem family life. He had friends in order to redeem friendship. He ate in order to redeem eating. He suffered in order to redeem suffering. He died in order to redeem death. The list can go on and on, but the point is that whatever He did, He did as the Divine Redeemer, taking both ordinary and extraordinary actions and supercharging them with sanctifying power.

Realizing Our Beliefs

This principle helps us to understand why He lived the “Hidden Years” of His life, seemingly doing nothing but living an ordinary life. He did not just one day, as Pope Benedict XVI is fond of saying, pick up the mantle of Redeemer. It was Who He was the moment He took flesh to Himself. We might be tempted to file this away as an interesting reflection on the truth of the Incarnation, as something that we simply believe, without taking the time to realize it.

The necessity of allowing our beliefs to be realized is at the heart of theology. What I mean by this is that it is not enough to merely intellectually assent to some truth (that is belief), it must become realized by becoming an active principle by which we live our lives. St. Thomas Aquinas is not a saint because he wrote the Summa, he is a saint because he lived the Summa. He modeled his life after the Church’s first theologian, St. Paul.

St. Paul believed in Christ’s full redemption and made it the principle by which he lived his life. By way of the Galatians, he instructs us to do the same thing when he said “it is no longer I who live, but Christ Who lives in me; the life that I live in the flesh I live in faith in the Son of God…”

We must first fully grasp that when St. Paul says this, he means it literally. He is not talking about how he tried really hard to imitate Christ and got so good at it that he acts a lot like Him. He means it quite literally that it is no longer his own life that animates him, but instead the life of Christ. By exercising his faith in Christ as full-time Redeemer, he has become another Christ in the world and calls us to imitate him in order that we too might say the same thing.

Linking Our Lives to Christ’s

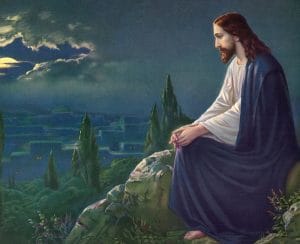

In short, the secret is that we must link our lives to Christ. This happens not in some abstract way, but by linking each moment of our everyday lives to the moment in Christ’s earthly life that “matches” it. This might still sound a little too abstract, so let’s take an example.

Let’s suppose that I just found out that a friend of mine has told a group of people something that I wanted to remain a secret. I feel betrayed. Rather than wallowing in that, I go to Christ in His moment of betrayal and speak with Him about the situation. When He experienced His betrayal, being God, He also foresaw this moment in which I would be betrayed. He submitted to it in order to redeem this moment for me. He has already won for me whatever graces I am most in need of. I simply need to show up with my divinely bestowed claim ticket to receive it. Still, it is His life, not just in the abstract, but really which moves me to respond in accord with the Divine Will.

Returning back to Athanasius’ point, you cannot find a single moment of your life that does not link up to Christ’s. Studying His life in the gospels is obviously helpful in making the connection, but it is not absolutely necessary. You can just as easily tell Our Lord, “I unite myself to that moment in Your life when you were hungry and ask for the grace not to be hangry in my situation” as go to Him when He is hungry after fasting in the desert. In either case, my willingness to go where Christ has already “remembered” me is the cause of the redemption and sanctification of the present moment. This is why every saint counsels the necessity of meditating upon the life of Christ. *****

Doing this occasionally is very fruitful, but once it becomes habitual, you will become a saint. The life of Christ and your life become practically indistinguishable as you draw all of your movement from His life such that Christ re-lives His life in you. This is what St. Paul was talking about. He started by exercising Faith in the Jesus as the Son of God Who died for him and then carries all of that to its logical conclusion by uniting His life at each moment with Christ’s. It is no longer I who live, but Christ Who lives in me!

***Seeing each moment of Christ’s life as a mystery in which I participate through prayer and receive graces He has already won for me specifically is at the heart of adopting this habit. It is Blessed Columba Marmion who has worked out the theology surrounding this, but I have summarized his thought in a previous post.