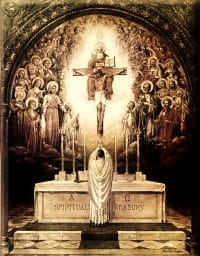

As Christ panned the landscape from His throne upon the Cross, He saw both friend and foe. The foes included not just the Roman and Jewish leaders that wanted Him dead, but the demons who had incited them to carry out His execution with the maximum amount of cruelty. Likewise he saw not just His Mother, St. John and the holy women, but also all of His friends throughout the ages that would willingly join Him. From the vantage point of the Cross, He saw a great battlefield forming before Him. He saw very clearly who His real enemies were and asked for forgiveness for their pawns. The spiritual combat that had begun in the Garden with Adam and Eve reached its zenith when the New Adam and the New Eve finally crushed the head of the Ancient Serpent. A new weapon, the Cross had been introduced. For the Cross was a key not only heaven’s opened not just Heaven’s gates but a portal into hell. No longer outgunned, the Christian grasps the Cross like the hilt of sword and chases the demons back into hell. Calvary is the terrain over which all spiritual combat traverses. This truth is almost self-evident. It is perhaps the “almost” that causes us to miss a very important corollary. Just as the demons were actively engaged on the field of Mount Calvary, they are still actively engaged in the Mystical Calvary, that is, the Mass.

Active and Conscious Participation and Spiritual Combat

The Second Vatican Council exhorted Christians to “active and conscious participation” in the Mass. The “activity” is not on the part of more ushers, lectors and extraordinary ministers of the Eucharist, but in the hand to hand combat begun on the hill of Calvary and continues over the pews of our little parish churches. If the Mass is what we profess it is, the sacrifice of Christ made present to us explicitly so that we might participate in it, then it also demands that we take a side in the great battle and engage. This is the activity of the Mass. The “conscious participation” is the awareness of what we are actually entering into. The Mass is a great battlefield in which each and every Christian engages in spiritual combat—not just in some abstract sense, but in actual hand to hand combat. And, as in all spiritual combat, knowing you are engaged in a battle is, well, half the battle. Once we become aware of it, we realize how we have known it all along. Obviously there is a great ideological battle that has taken place that has obscured this truth and so we must begin by setting our minds and hearts firmly upon this truth.

Hand to hand combat is never just a “spiritual” thing but something real and practical. First there is the battle that occurs remotely. The great enemy of mankind hates the Mass and will do anything he can to keep us from being there. Obstacles are thrown up left and right to leaving on time. Otherwise peaceful families suddenly experience strife. Family members experience agitation and begin to quarrel. Accusations are thrown back and forth. The difficult child becomes more difficult while the impatient parent becomes more impatient. Clothes and keys can’t be found. The battle lines have been drawn and Pilate is reminding you that he has the power to make it all go away. Many will fall by the wayside because, after all, “what is truth?” Then there are those who, having their peace stolen, will set out on the way, leaving the Cross behind. Calling to mind what the Divine General did, the true soldier of Christ embraces the Cross and sets out on the Way. Knowing that he is headed to the Front is not enough however. He will serve as Simon of Cyrene by offering his cross for those in the first two groups who may not have the strength to carry theirs.

Once the Christian arrives at the Front, he is confronted with a new temptation—“to come down off the Cross” (c.f. Mk 15:30). In fact this is the primary weapon that the demons use against us. He will throw every distraction he can before our imagination. “What are they wearing?” , “Look at her! Look at him!”, “why doesn’t she pay attention to what her kid is doing?” “What do I need to do after Mass?”, “What is Father talking about?”. The demons coordinate their attacks, tempting one person to do something and then setting the judgment in the mind of another. You may have made it to the Front, but they can neutralize you through distraction. Again in recognizing it for what it is we have won half the battle. And with recognition, we derail the train of thought and hop back on the Cross with Christ Who has been waiting there for us from all eternity. This is a battle and each time we join Christ on the Cross we not only draw deeply from the fruit of the Tree of Life but are dealing a blow to the Evil One.

Take note Pastors, Liturgical Coordinators and Music Directors. This is why the liturgy should be completely devoid of any novelty. A well-disciplined army, one that has drilled so often that the battle itself becomes second nature, is a successful army. The war may be over, but we are trying to limit casualties in the mop-up operation. Novelty on the part of priests and coordinators only serve to distract and cause the army to fall from formation. So too with the music, it should be chosen not for its entertainment value, but for its ability to keep us engaged in the battle.

In all that was said so far it might seem then that the whole purpose of us going to Mass is to avoid distraction so that we can focus on what is going on. That is to see the battle only in terms of defensive tactics. The primary purpose of the Mass is to enable each one of us and all of us (that is the Church as a whole) to make the sacrifice of the Cross our own by way of participation. And this participation involves three different postures, each one based on those found at the Foot of the Cross on Calvary.

The Three Postures

The first posture is the Marian posture. Those who unite themselves with the Mother of God and adopt this posture are those for whom Mass involves personal suffering. Think for example of the special needs parent and child. Or think of the person who had great difficulty in crowds. Or the person who is undergoing a great personal crisis. Or even the parents of young children for whom 60 minutes sitting still in one place is a great challenge. These people are actively suffering with Christ

Those with the Marian stance are not only suffering with Christ, they are in a very real sense, suffering for Christ. They could just as easily decide that it is simply too hard to go to Mass and skip it. They may even be justified in so doing. But their love for Him precludes it. That is why the second posture, that of the holy women, is also necessary. The holy women at the foot of the Cross were there not only because they loved Christ, but because they also loved His Mother. It was not just His suffering that moved them, but hers as well. Their offering to Christ was one of prayer and support for Him and His Mother. The holy women (and men) of the Mystical Calvary, rather than giving in to the temptation to judge the Liturgical Marys in their midst, they support them through their understanding glances and prayers.

Finally, there is a Johannine posture. Motivated by a deep friendship, the Church’s first mystic was moved to great sorrow for his sins and a loving contemplation of the events unfolding before him. The Liturgical Johns work hard to remain in this posture throughout the entire Mass, moving from sorrow to thanksgiving as they try to penetrate ever deeper into the Mystery unfolding before them.

Before closing, it is important to mention that although the three postures are mutually exclusive, it does not mean you must select one each time you go to Mass. Very often God makes it abundantly clear which role you are to play in a given Mass and, even, during a particular part of a given Mass. In other words, you will always be playing one of those parts, but not always playing the same part.