Yesterday, July 13th, marked the 104th anniversary since Our Lady visited three children in Fatima Portugal and donned the prophet’s mantle warning of the dire consequences that mankind was to face for the next century. Her prophecy that “Russia will spread her errors throughout the whole world” remains the most relevant today. For Our Lady was not merely warning against Communism per se but was warning about the errors upon which Communism rested. Our Lady of Fatima was telling us that the next great battle the Church would face would be against Marxism.

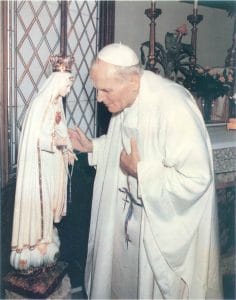

Our Lady anointed as her “helpmate” the second great prophet of the 20th Century, John Paul II to assist her. He had given his papacy, like his entire life and priesthood, to Our Lady. He even adopted as his episcopal motto, Totus Tuus (“all yours”), to show his total consecration to Mary. So, when on May 13, 1981, the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima, just prior to giving his Wednesday Theology of the Body lecture and the announcement of the founding of the Pontifical Institute for Marriage and Family, the Pope was shot he saw it as confirmation of his prophetic mission. He said that “one hand pulled the trigger while the other guided the bullet” away from his major arteries and organs. Our Lady had directly intervened so that John Paul II could carry out his sacred mission of stopping the spread of the “errors” of Russia. He eventually dealt a decisive blow when he played an instrumental role in the destruction of the Eastern Bloc.

It is tempting to think that Communism died when the Berlin Wall fell, but nearly 2 billion people still labor under Communist regimes. As one of them, China, continues to exercise its hegemonic aspirations, and the errors of Russian continue to spread far and wide, it becomes increasingly important to both understand and counter these errors.

Marxism as Identity Theft

In his Encyclical Divini Redemptoris, Pope Pius XI spoke of Marxism as a “Satanic Scourge”. The reason for this is that it strikes at God by attempting to obliterate His image in man. It overwrites human nature as co-Creator with God (proletariat vs bourgeois) and as men and women in marriage (exaggerated equality between the sexes). The Marxist revolution shifts away from the family, an image of the Trinity, as the fundamental unit of society towards the individual. The individual is merely a cog for the collective without any inherent dignity. It employs the Sexual Revolution as the means for bringing this about—divorce, abortion, contraception, sexual promiscuity even homosexuality (since nothing un-natural)—all permitted and promoted in the name of liberation from the family and human nature.

Likewise, complementarity is replaced with inherent conflict. A perpetual conflict between victim and victimizing classes is set up and Marxism delivers Messianic prophecies of peace that removes even the need for government. Everyone will be equal except, of course, for those who would be more equal than others. To reject the inherent hierarchy in creation leads to anarchy.

This is where John Paul II enters the scene. As he told his friend Henri de Lubac, he saw it as his mission to put an end of the pulverization of the human person that had its roots in Marxist thought: “The evil of our times consists in the first place in a kind of degradation, indeed in a pulverization, of the fundamental uniqueness of each human person…To this disintegration planned at times by atheistic ideologies, we must oppose, rather than sterile polemics, a kind of ‘recapitulation’ of the inviolable mystery of the person.”

The means by which he would accomplish this “recapitulation” is his Theology of the Body. He would flip the materialistic atheist’s vision of man as nothing but a collection of atoms at the service of the collective on its head. He would say that the material exists to make the immaterial present. Man was not just a body, but the body revealed man. John Paul II would offer his Theology of the Body as the foundation for solving the identity crisis brought about by Marxism.

A man or woman’s identity can only be received by knowing where he or she came from. Are they simply an accident of biology, or worse, an accident of a creation in lab? Or, were they willed from the beginning as a directly willed act of love, the crown of creation and very good? Karl Marx says they are the former while John Paul II affirms the latter.

Theology of the Body as Antidote

Theology of the Body restores the Christian vision of man’s origin through the three moments of Original Solitude, Original Unity and Original Nakedness. Man was made to be different from and superior to the animals. He does not come from the animals but instead is superior to them from the beginning and capable of being in relationship with God. This Original Solitude is not all because the man Adam was also made to be in a self-giving relationship with the woman Eve in Original Unity. Through the Original Nakedness in which they are “naked without shame” the two visibly see their vocation to love.

But knowing the beginning is not enough for our identity. We must also know our history. This history is not marked by conflict between victim and victimizer but Fall and Redemption by Christ who became a victim so that we didn’t have to. Christ came to take away all of the coping mechanisms that modern Marxian psychology offers and gives to us true freedom that Marxism can never give.

Finally, to know our identity, we must know our destination. Marxism controls and manipulates people through a fear of death. It always try to take away man’s vision of where he is going. The last 16 months have made this abundantly clear. But Christ came to take away the fear of death and to clear our vision to our supreme calling, to be caught up in the life of the Trinity with the Communion of Saints. There is no absorption into the “Collective” but a blossoming of personality such that we become who we were made to be. John Paul II’s Eschatological Man provides the vision and spurs our desire to journey there.

It is not a coincidence that Our Lady promised that once the errors of Russia were defeated, the reign of the Immaculate Heart would be achieved. The love with which Mary loves, a love that is marked by purity, will invade the hearts of mankind–and Theology of the Body supplies the blueprint for that vision.