History, it is said, is written by the victors. Whether this dictum is absolutely true or not can be debated. What cannot be debated is that history is always rewritten by those seeking victory. Historical rationalization allows the combatants to demonize their enemies, therefore justifying the annihilation of the culture. Who can doubt that this has been a weapon in the arsenal of the Church’s enemies throughout the last few centuries? As of late the enemies of the Church have attempted to rewrite the annals of history in order to paint the Church as indifferent, if not positively in favor of slavery. In order to show this to be a lie, we must arm ourselves with the truth.

We must first set the stage by examining the world into which Our Lord took flesh. Christianity arose. Approximately 1/3 of the population of Ancient Rome were slaves. All manual labor was performed by them. In the fiefdom of the paterfamilias they were viewed as human property, essentially chattel, and held no rights. In this regard Rome was no different from any culture prior to the arrival of Christ, including those encountered by the Jews (more on this in a moment). Slavery was always viewed as acceptable and absolutely no one questioned the institution. The only places it wasn’t practiced were those places that could not support it economically because the cost of maintaining the slaves was greater than their output. This is an often overlooked, but nevertheless very important, point for two reasons.

Ending Slavery as a Practical Problem

First, given that slavery was ubiquitous, ending it as an institution would take power—either physical or moral. This is why when Moses gives the Law to ancient Israel it says nothing condemning slavery but only how slaves were to be treated (c.f. Exodus 21:26-27, Deut 23:15-16). And how they were to be treated was far greater than any other ancient culture. This does not make it right or whitewash the immorality of it, but it does see how God was setting the stage for a moral revolution that would eventually topple slavery in the Christian world. To condemn it would have been to shout into the wind. He chose not an ethic, but to form an ethos. And some of the different Jewish sects like the Essenes caught the ethos sooner than others and refused to practice slavery.

Those who often try to change history forget that Christianity is a historical religion. What this means is that God acts within specific cultures and in specific times. Without understanding the cultural context, we will fail to miss the principles upon which His commandments are founded. Any criticism of St. Paul for example must first include the cultural context in which he wrote. To label his household codes (c.f. Col 3:18—4:1; Eph 5:21—6:9) as anything other than revolutionary is to trivialize what he is saying. He demands that the slaves be treated justly (implying they are people with rights and not property) and that they will have to answer for how they treat their slaves. While it might be implied that just treatment would include freeing them, he does not explicitly call for this. This may insult our modern sensibilities towards anything other than absolute freedom, but it is because if the slaves were treated well by their masters, especially in the harsh Roman culture, then they might actually be better off remaining with their masters. Many of them would have had nowhere else to go.

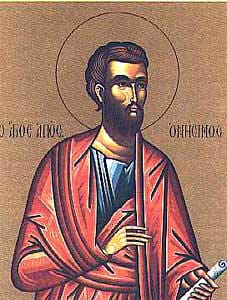

There is one particular case in which St. Paul did call for the release of a slave because he did have a better place to go (see Philemon 8-14). Onesimus was a slave who stole money from his master, Philemon, and escaped to Rome. When he ran into hard times in Rome, he found Paul whom he met at his master’s home in Colossae. They developed a friendship and Onesimus was baptized. At this point, Paul tells him he must return to his master and gives him a letter to present to his master. This is the point where we must read the letter carefully to see what St. Paul was saying. He tells Philemon that “although I have the full right in Christ to order you to do what is proper, I rather urge you out of love”. Paul is saying that he could order Philemon to release Onesimus because it is “proper” (i.e. slavery is wrong). But instead he wants him to release him out of love for his Christian brother. The only reason he sends him back is so that “good you do might not be forced but voluntary.” He wants to give him the opportunity to do the right thing for the right reason based upon a fully Christian ethos.

And based upon the history of the Church, Philemon responded just as St. Paul had hoped. First, because the letter was saved for posteriority, that is, Philemon would not have saved a letter and distributed it if he did not comply with it. Secondly because we find in the Constitutions of the Holy Apostles that Onesimus was ordained by St. Paul as the bishop of Macedonia. Onesimus is the first beneficiary of the revolutionary view of mankind set in motion by the God made man.

The Impossibility of Judging Christianity by Its Own Principles

The second reason why we cannot overlook the fact that slavery was ubiquitous in the ancient world is that, in truth, without Christianity slavery would never end. If we flash forward 1000 years to the end of the first Christian millennium we find that slavery is non-existent in the Christian world. This condition continued through the Middle Ages so that by the 15th Century all of Europe is slavery free except for the fringes in the Iberian peninsula (under Islamic control) and in certain areas of Russia. The Muslims were indiscriminate as to who they enslaved—black or white it did not matter. Once they were run out of Spain and Portugal they went to Africa and joined in the already indigenous slave trade, that is, Africans enslaving and selling into slavery other Africans. Again, another often overlooked fact that the African slave trade was already an institution long before the Europeans arrived in the late 15th Century.

With slavery practically eradicated in Christendom, then how did slaves end up in the New World? The Spanish and Portuguese Christians, living under an Islamic regime for nearly 700 years, had grown accustomed to it. So when labor proved itself both lacking and necessary in the New World, the Spanish, Portuguese and eventually English turned to chattel slavery once again. They did this against the very clear and repeated condemnations from the Church. Beginning in 1435 with a bull Sicut Dudum, Pope Eugenius IV demanded that Christians free all enslaved natives of the Canary Islands within fifteen days or face automatic excommunication. Over the next 450 years, the Popes unequivocally prohibited the enslavement of any peoples (see this link for a complete list). With fists full of mammon covering their ears, many of the so-called Catholics simply ignored the Church’s teachings, especially because there was no real way of enforcement.

And herein lies the reason why the facts cannot be overlooked. The Church’s teaching on slavery as intrinsically evil has been and always will be unchanging. St. Paul’s Magna Charta of Christian brotherhood in Col 3:26 is forever established. In this regard Christianity cannot be judged because to judge it, is to judge it based on its own principles. Put another way, only Christianity taught the evil of slavery and so you cannot judge the principle by the principle itself. What you can judge and absolutely should judge is Christians themselves for failing to live up to these principles. For that, many Christians themselves have failed miserably to protect the dignity of their fellow men. Parents sometimes are blamed for the actions of their children when there is a bad upbringing, but the clarity and insistence of the Church on this issue makes it clear that it was the children themselves who went astray. What must be absolutely clear is that without the Catholic Church, millions, if not billions of people, would be in physical chains today. No matter how the usurpers of our post-Christian society may try to paint the issue of slavery, that is a truth they must ultimately contend with.